Jean HELION « an eye that dreams »

1904 – 1987

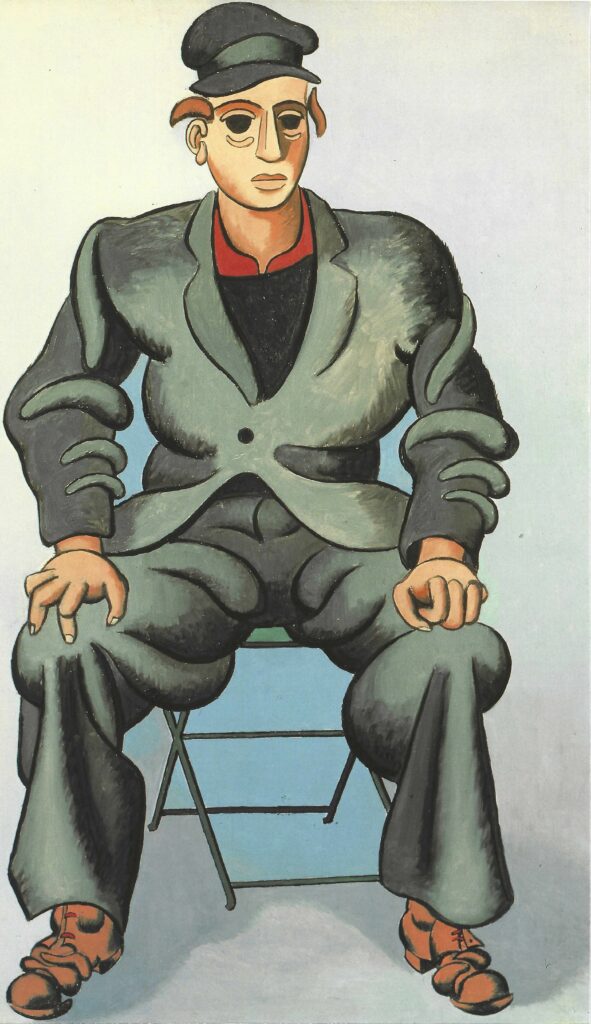

It is customary to present Jean Hélion as the very example of the abstract painter who went into figuration after the Second World War, against all the avant-garde, who then chose the abstract path in its various currents. The point is correct but simplifying insofar as before being an abstract painter Jean Hélion between 1924 and 1929 built a work of figurative painter, which, if it sometimes shows him very close to Soutine whom he admires (for example in L’homme assis of 1928)

reveals in his still lifes a mastery and a science of balance which prevents the assimilation of the first works to the beginnings of a painter seeking his way.

These still lifes generally treated very in pasto with dominanting red and blue are composed from the poor everyday objects that furnish the daily life of his studio: bowls, bread, soup tureen, bottles (see in particular Les 3 bouteilles of 1928)

chairs, table and the English horn, which he improperly calls trombone. A few portraits appeared here and there.

Three men have, during these years, a major influence on the young painter.

The Belgian painter Luc Lafnet, former Grand Prix de Rome, met in 1924 will teach him, “day after day what it is necessary to know to manipulate colors and bend them to a purpose” and will have him exhibited at “La Foire aux croûtes” at Montmartre.

The collector Georges Bine took him under contract in 1925 and acquired a large number of works from this period; a very fine ¾ self-portrait of 3⁄4 dates 1925 in a harmony of blue and green where the painter stands out on the steps of a staircase.

The third is the painter Torres Garcia, whom Helion meets and gives him shelter at home in 1926. The latter, who is thirty years older than him and is not yet the great abstract painter that we know, will introduce him to the great names of the world art and will show him around the significant exhibitions.

1929 – 1932

It was during a trip to the Pyrenees in May 1929 with Georges Bine that Hélion produced his first abstract compositions on bristol paper, all of the same size 61 x 50 cm where curves and rectangles are framed by black lines. This process was continued on canvas after his return to Paris to the end of 1929.

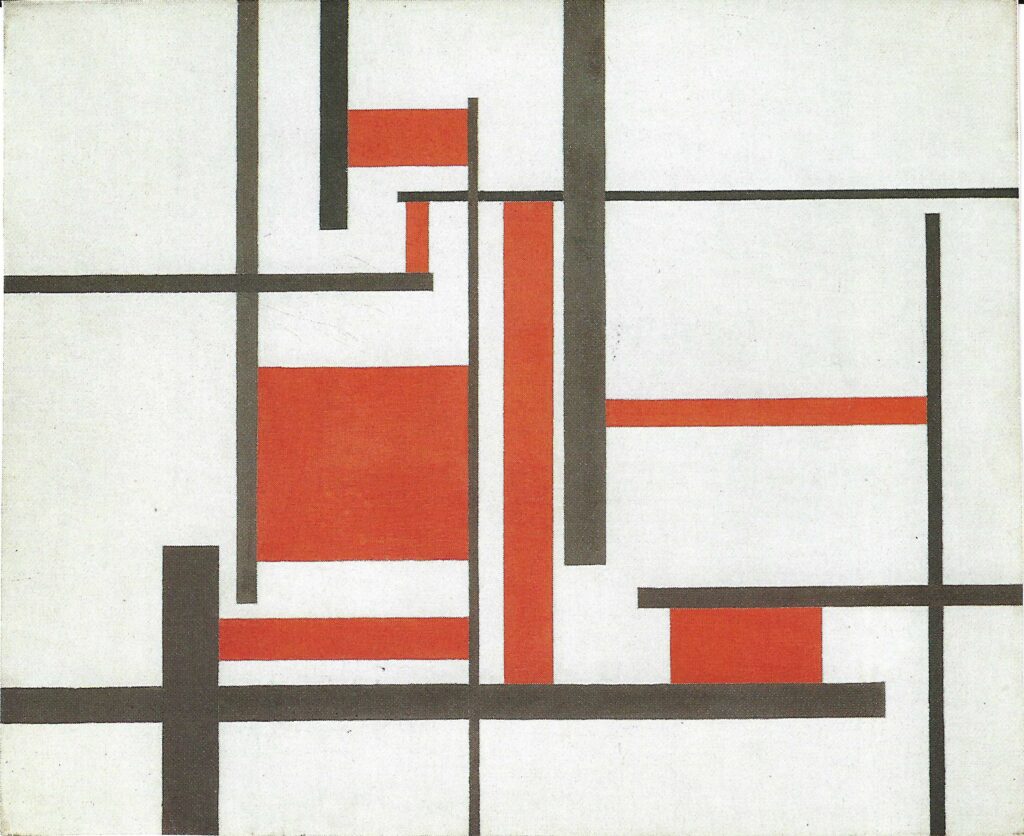

1930, complete change. After the discovery at Torres Garcia’s at the end of 1929 of a painting by Mondrian Hélion becomes an outright follower of neoplasticism and his compositions from 1930 – 31 are in strict conformity: pure primary colors plus black, white, gray, treated in flat areas strictly limited by vertical or horizontal black lines drawn with a ruler. La composition constructiviste of 1930 or La composition orthogonale of the National Museum of Modern Art are proper examples.

This was the time when Hélion was part of the Art Concret movement around Van Doesburg whose manifesto states: “The work of art … must not owe anything to nature, nor to sensuality, nor to sentimentality”.

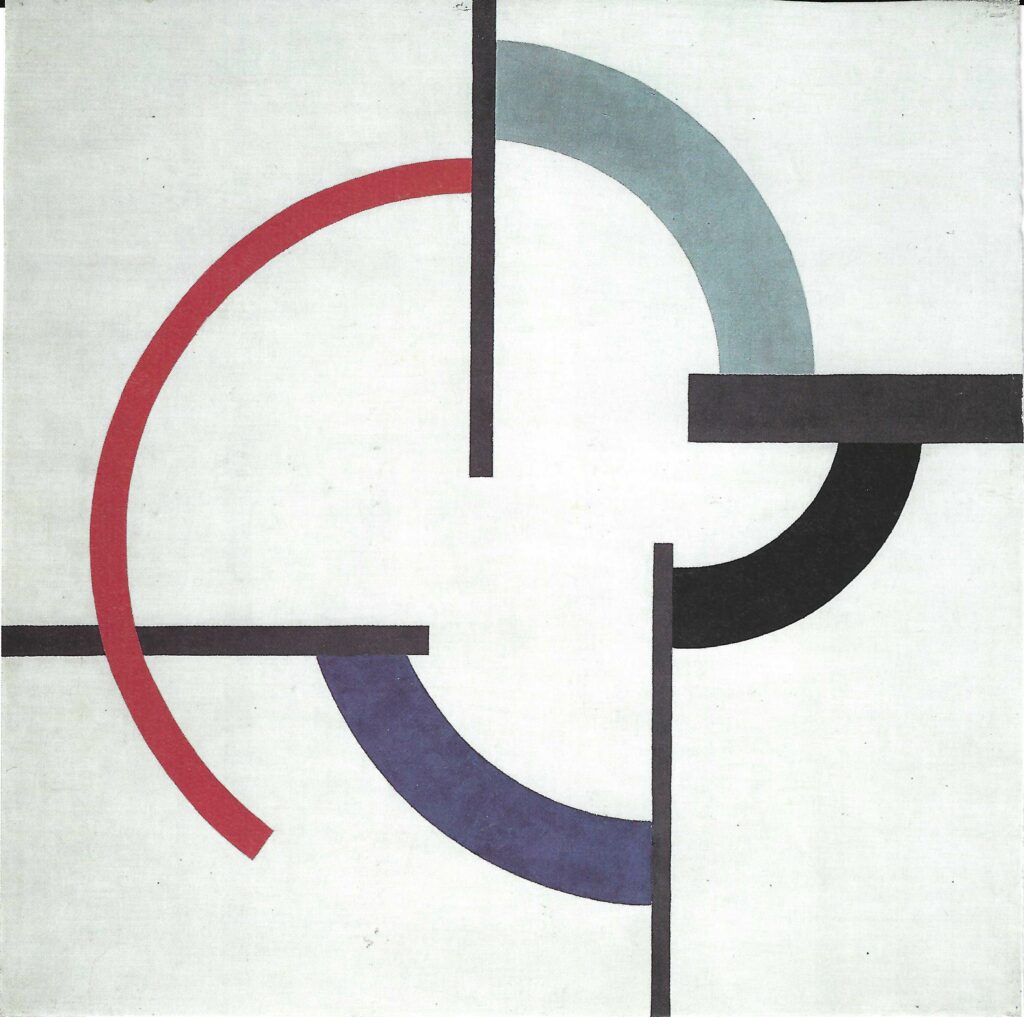

Les tensions circulaires of 1931-32 do not depart from the strict concepts of concrete art insofar as, far from wanting to imitate nature, they are drawn with a compass. Art Concret dissolved in 1931. Abstract painters find themselves in a much larger and therefore much less rigorous movement called Abstraction – Creation.

Hélion met there the pioneers of abstract art, Delaunay, Arp, Kupka, Mondrian, without abandoning the strict rules of his compositions.

1933 – 1938

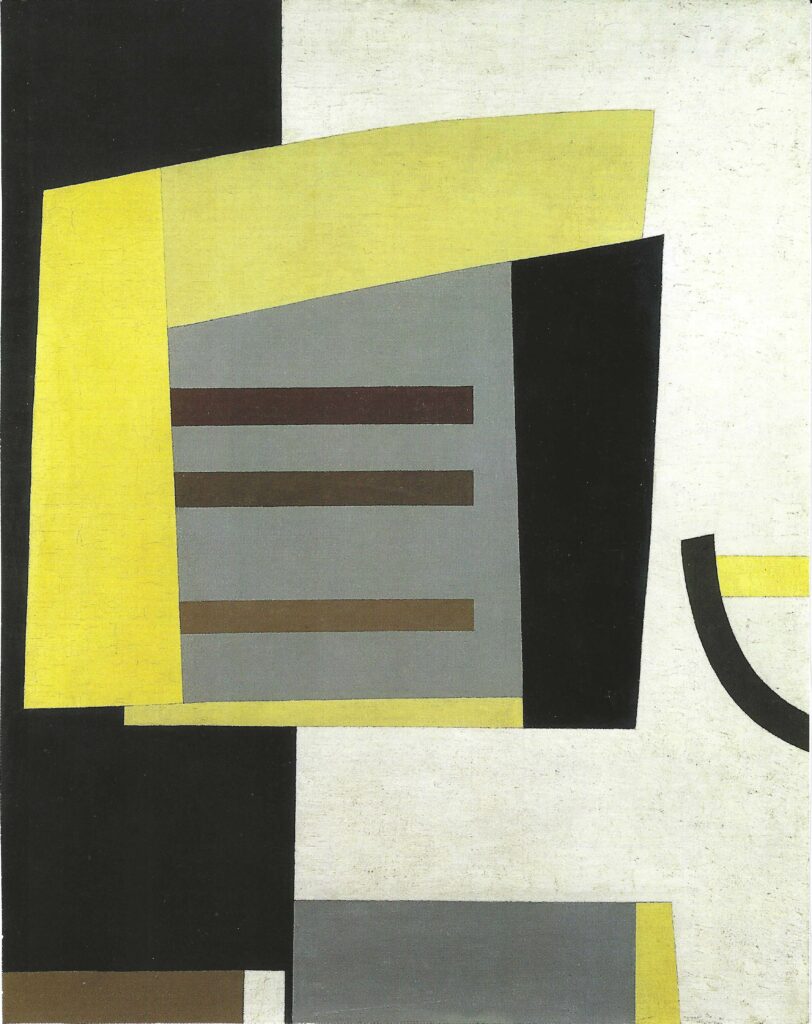

1933 is an important year for Hélion. There he conquered his independence and originality with the Equilibres series, a grouping of truncated conical shapes connected by curved lines, all giving the impression of pivoting around an axis. This complex composition stands out against a generally pale gray plain background. A no less important change occurs in the very concept of the pictorial subject in the painter’s mind. He who, in 1930, rejected any reference to nature returned to it conceptually long before it was perceptible in the painted work. In March 1933 he wrote: “The superiority of nature is to offer maximum complexity of relationships. It is towards this that I am striving”.

In 1934, these forms become separated and proliferated, acquiring a relief obtained by variations in color intensity.

From November 1934 to the end of 1938, their number was reduced, these forms regrouped, constructed like sculptures. One has the impression of witnessing the birth of still vague human forms. The painter calls them figures. The approach is very well analyzed by Hélion in his day to day writings.

On November 20, 1934, concerning the large canvas (1.60 m x 2.06 m) named Trois figures: “It seems that this painting represents characters: I don’t have a problem with it, I’m only sure that it contains individuals there leading a life together without altering their personality. If I am not mistaken, it makes a lot of sense”.

On January 10, 1935 he wrote: ” I am undertaking a recovery of my compositions, like the first man, on all fours, will developpe two feet and two hands”.

On April 28, 1935, speaking of Ile de France at the Tate Gallery in London, he wrote: “The more I advance the more the call of nature becomes evident … the volumes will have to become complete: objects, bodies. It will soon be the inevitable tip of a natural nose and the passing into a new naturalistic era”.

This “humanization” of the subject is particularly noticeable in the beautiful 1938 painting entitled Trois figures. Since July 1936, Hélion, who married an American woman (his second wife), spent most of his time in the United States, where he exhibited for the first time in 1933. It was in the United States that he developed the most striking works of the year 1939.

1939 – 1942

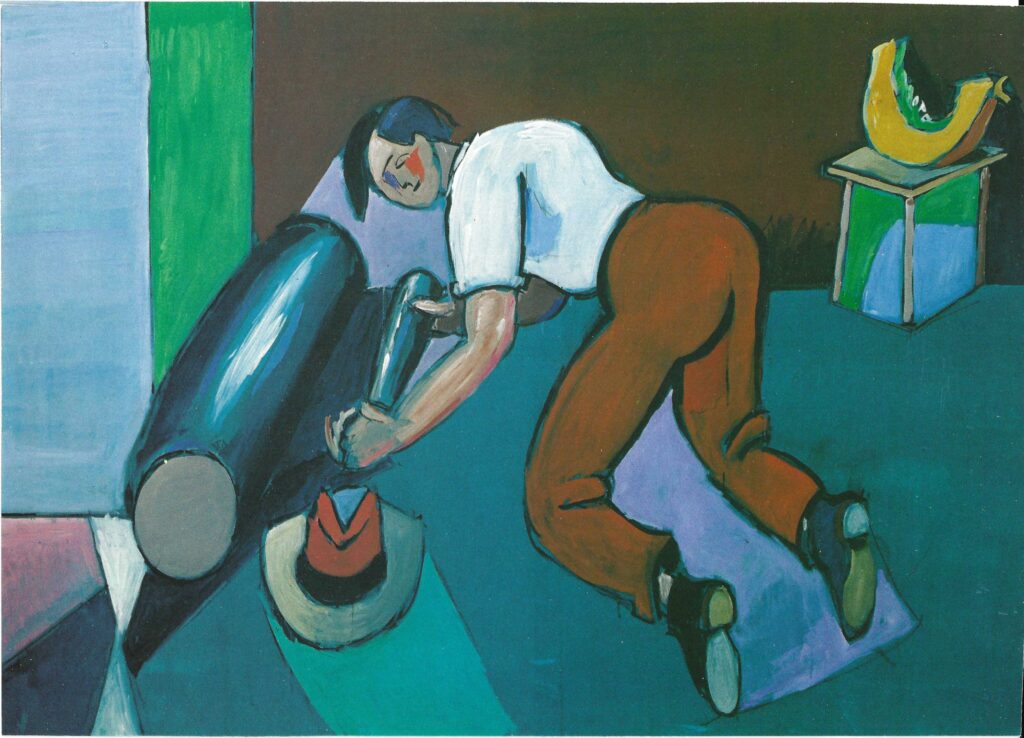

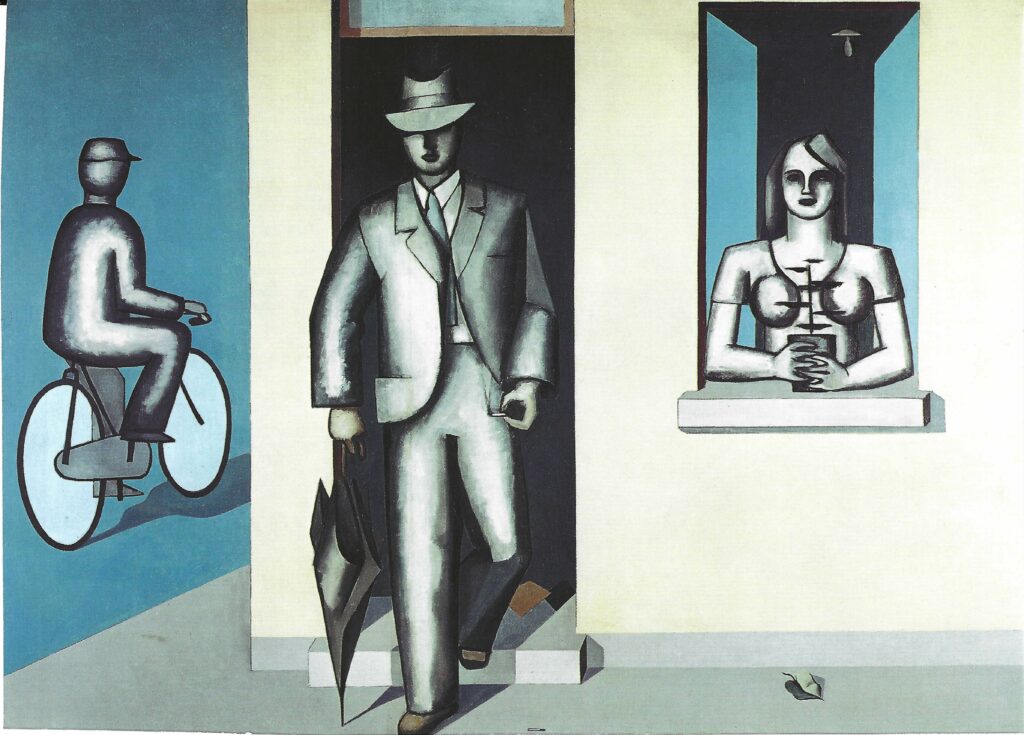

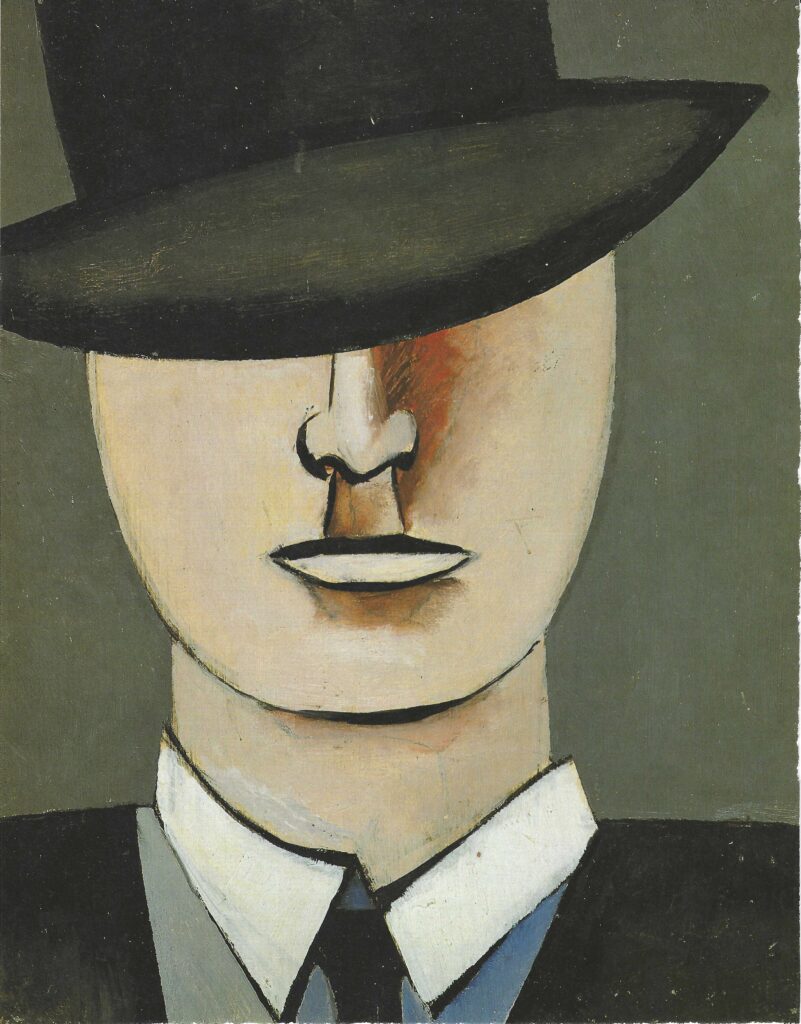

1939 was a pivotal year for Hélion. Between April and September, he produced his last abstract work Figure tombée and simultaneously his first figurative work since ten years Au cycliste. These two major works are at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris. Very similar in size, in three parts composition using very similar vertical planes. Unlike Figure tombée, which is rich in colors, Au cycliste moves in a harmony of blue and ocher where characters with tubular shapes are available in subtle shades of gray. In October Hélion begins a figurative series of some twenty variations on the theme of the head of a man wearing a hat. These characters make up the series of Emile, Edouard and Charles.

“Emile is a full-face character, his round hat blinds him, he wears collar and tie […] Edouard is in full profile with a boater, an orange bow tie […] Charles, seen from behind, light gray felt hat… “

Hélion was in the United States when the Second World War broke out. He returned to France in January 1940 to be drafted there.

Taken prisoner in June 1940, he escaped in February 1942 and, after various adventures returned to the United States in October 1942 and engaged in anti-Nazi propaganda through a series of lectures and the publishing of a very successful book They shall not have me.

1943 – 1946

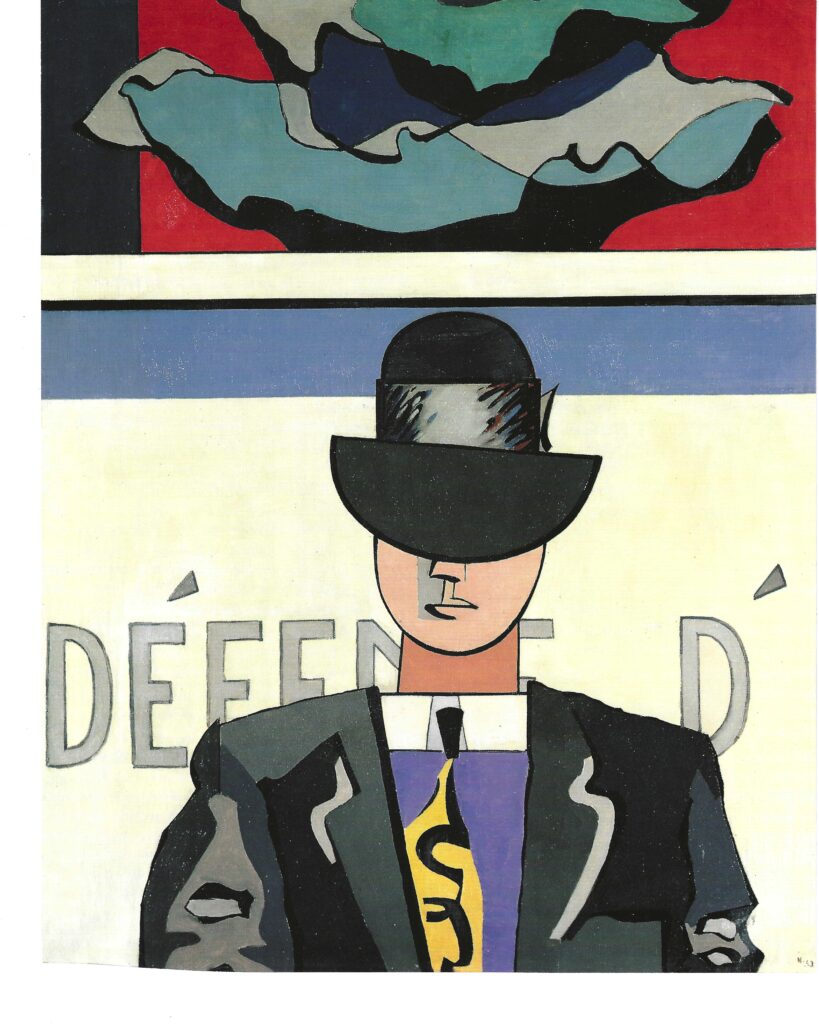

When Hélion began to paint again in 1943, quite naturally other men with hats, other men with umbrellas, came back under his brush. One particularly notes is the defense of ’…, an Emile in front of a wall bearing the inscription Défense d’ …, often interpreted as an ironic reference to the intransigence of abstract movements with regard to nature.

The shapes of these angular figures, treated with large flat aeras, often come from this vocabulary of abstract signs developed in the 1930s. Little by little, other figures appear: the saluter, the lighter, the man with the empty glass, the half-naked painter and fair-haired women generally seated holding their chins and spreading their legs wide; La fille aux pieds dans l’eau at the Indianapolis Museum is a proper example.

After his return to Paris on April 10, 1946 (Hélion notes in his diary “return to Paris: joy”) these forms become fuller and fuller, free, relaxed, happy. Loaves of bread, which he dreamed during his captivity, also appear.

1947 – 1948

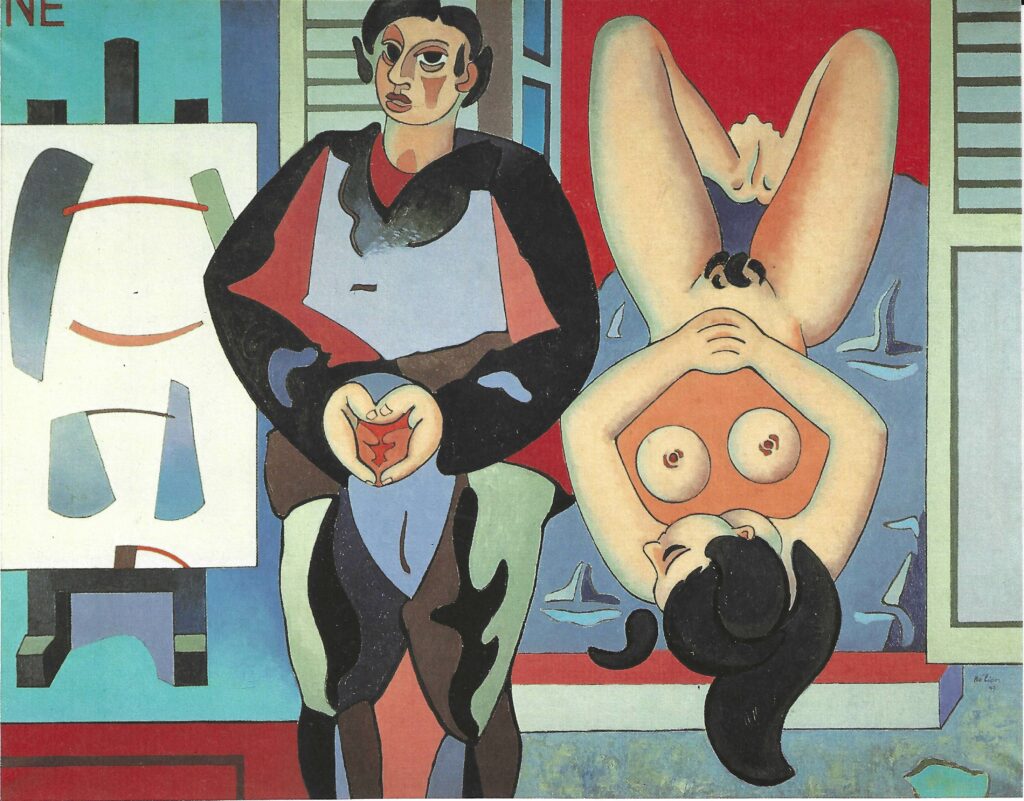

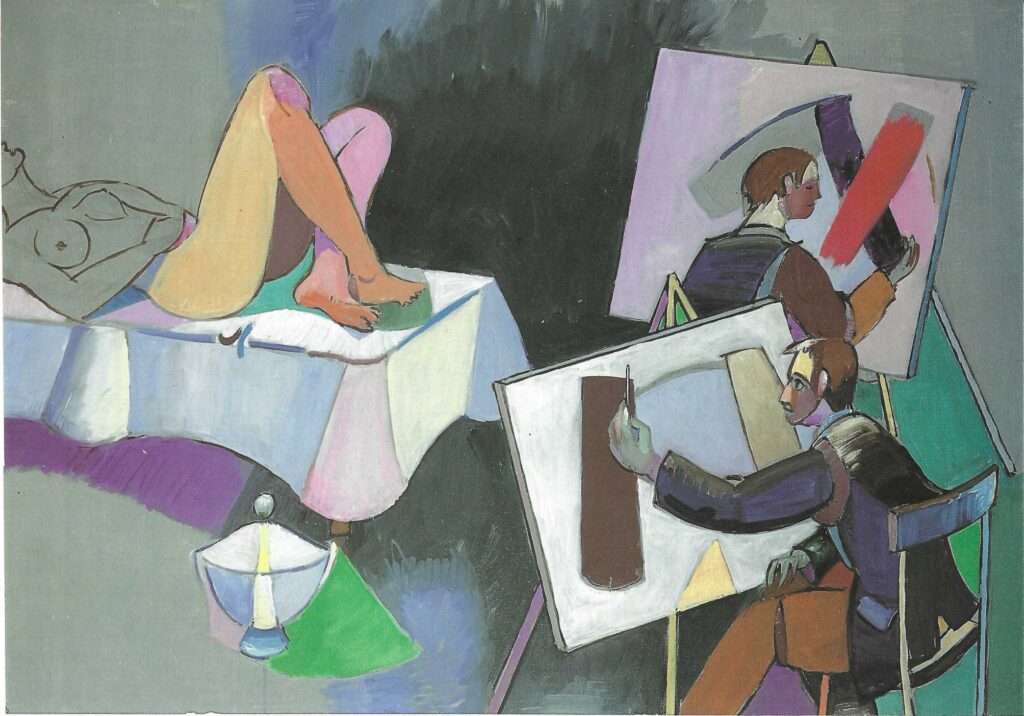

In January and February 1947, Hélion produced two large paintings Les trois nus and A rebours. In the latter, which is at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the painter represents himself between an inverted nude (whose opulent forms borrow a lot from the vocabulary of signs developed during the abstract period) and an abstract work whose architecture evokes a human body. With these two works, Hélion is intimately aware of having brought the lyrical figuration to which he has devoted himself since 1945 to near perfection. “[These two paintings] … seem to me to be the most complete and vivid paintings that I have produced. I would like to be judged on that “.

This will be achieved in May 1947, Hélion presents his figurative works at the Galerie Renou et Colle in Paris, Paris where he has not exhibited since 1938. With rare exceptions, the critics are very hostile. The painter then decides to analyze his mental process in a very self-demanding way: he wants to be a demiurge, by creating a world of forms that years of abstraction have taught him the alphabet, a world to exalt Man and from which man is rarely absent, either directly or through the objects that evoke him. In his October 1947 journal two sentences explain his project: ” Man, monument of himself”. Between his arms and legs, a cathedral of spaces and stained-glass”. And the next day ” In short, I dream of a Sistine Chapel in modern clothes and forms”.

The actors of this world that Helion will endeavor to create will be seated men, newspaper readers (which the painter calls newspapermen), female nudes, recumbent figures and models. The importance Hélion attaches to this great project is proved by the fact the two journals that he devotes to this project describing the paintings he creates. The first one, entitled Journal des hommes assis, des journaliers, des natures mortes, begun in September 1947, ended in September 1948. It lists five paintings of seated men, four newspapermen and twelve still lifes.

The five oils representing L’homme assis show him seated on a chair or stool, only the base of which can be seen; the legs wide open, the hands firmly placed on the knees evoke Ingres’ Monsieur Bertin, a purely formal resemblance because the seated man whose gaze slips away has nothing of the arrogance of the successful man depicted by Ingres for eternity. If the subject is figurative, the set of signs that defines it belongs to the abstract vocabulary which Helion perfectly maters. An excerpt from his journal clarifies his thinking: “Decipher an entire character using one of their own elements. Example: starting with the shape of a fold, find that shape and related shapes throughout the character. In L’homme assis that I work … exact relationship of the nose and the folds of the right leg”. This is written concerning the first painting in the series which belongs to the Lenbachhaus in Munich.

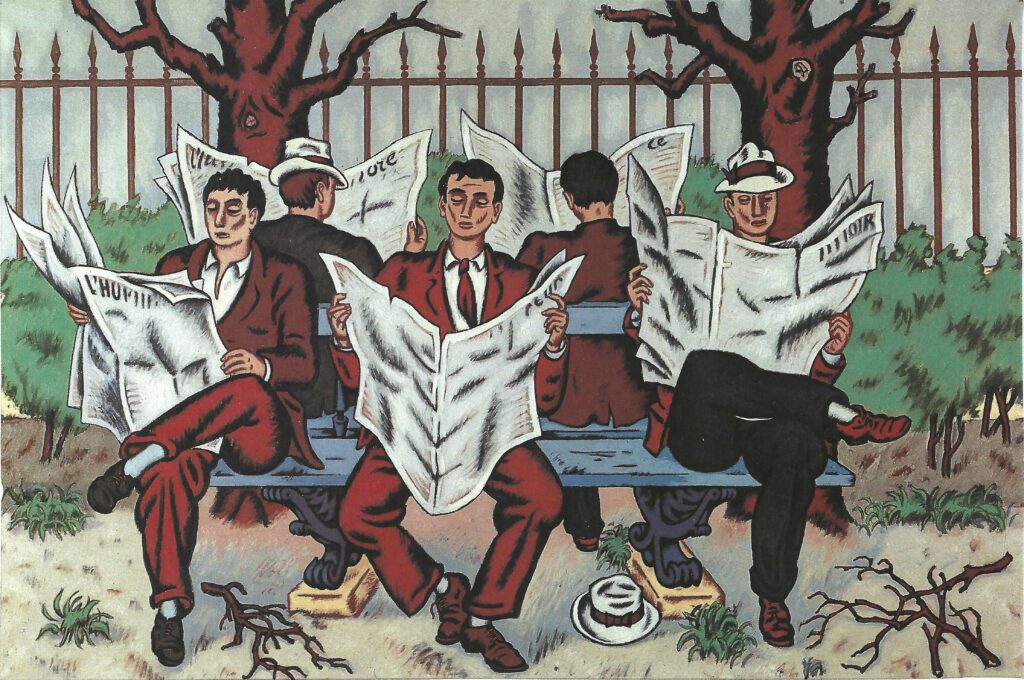

All these seated men painted during the last quarter of 1947 give an impression of monumentality which results essentially from the strict parallelism of the character’s legs and the unchangeable respect of the 2/3 proportion (from the top of the head to the seat) 1/3 (from the seat to the heels of the shoes). The theme of the newspaperman, defined as the state of the man who reads his newspaper, gives rise to four paintings which all show the reader standing sheltered behind his newspaper “his paper fortress”:

produced between January and September 1948, they are all in private collections. Their common feature is the emphasis on heavily underlined clothing folds in the shapes of drops of water, commas or crescents. At the same time, Hélion undertakes three paintings which he calls Scènes journalières. They bring together two readers, one on the right, the other on the left of the composition, meet a man seated in a doorway. One of these works belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York; one of a smaller size is at the Museum of Modern Art in Saint-Etienne; the third, the largest, is in one of the most famous French private collections. One can wonder about the symbolism of these daily scenes. A phrase from Helion helps to understand: “Men: judges, witnesses, sitting in the face of eternal problems. Readers who read newspapers and only find the Eternal”.

Before leaving the newspapermen, it should be noted that they will reappear in 1950 in a work that Hélion calls La grande journalerie. A large format (130 x 195 cm) this work is in the United States. Here the newspaperman is no longer alone and he is no longer standing. Five figures are seated on either side of a bench in the Luxembourg Gardens. The newspaperman is no longer alone, he is just as solitary; the paper fortress function that Helion assigns to the newspaper makes sense here. This is not open to the world, it is a withdrawn attitude

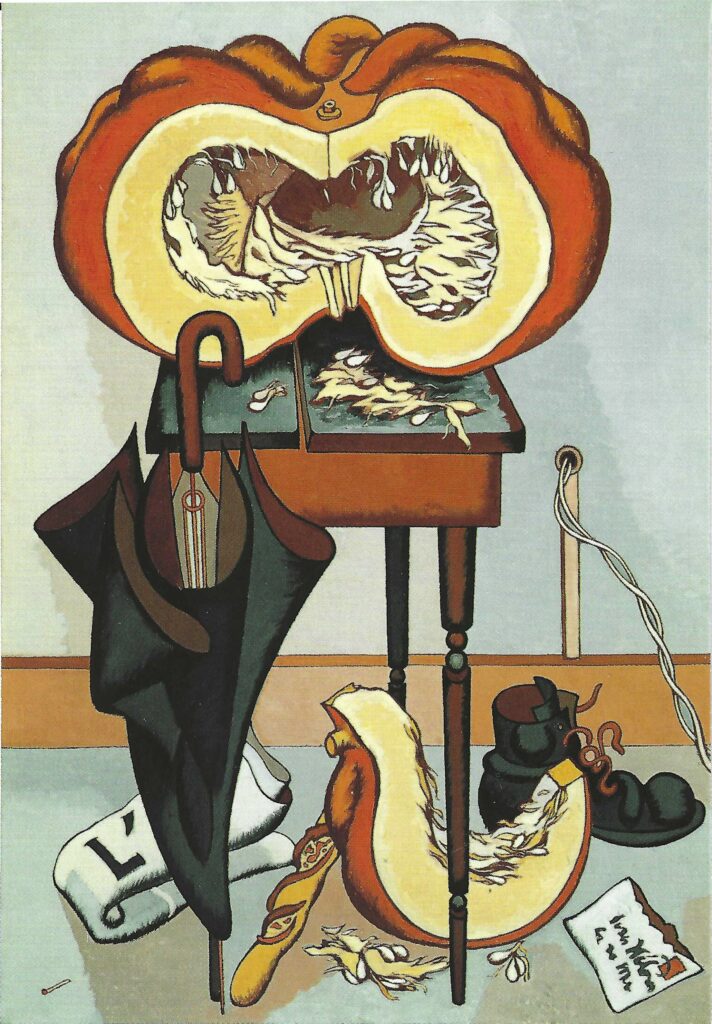

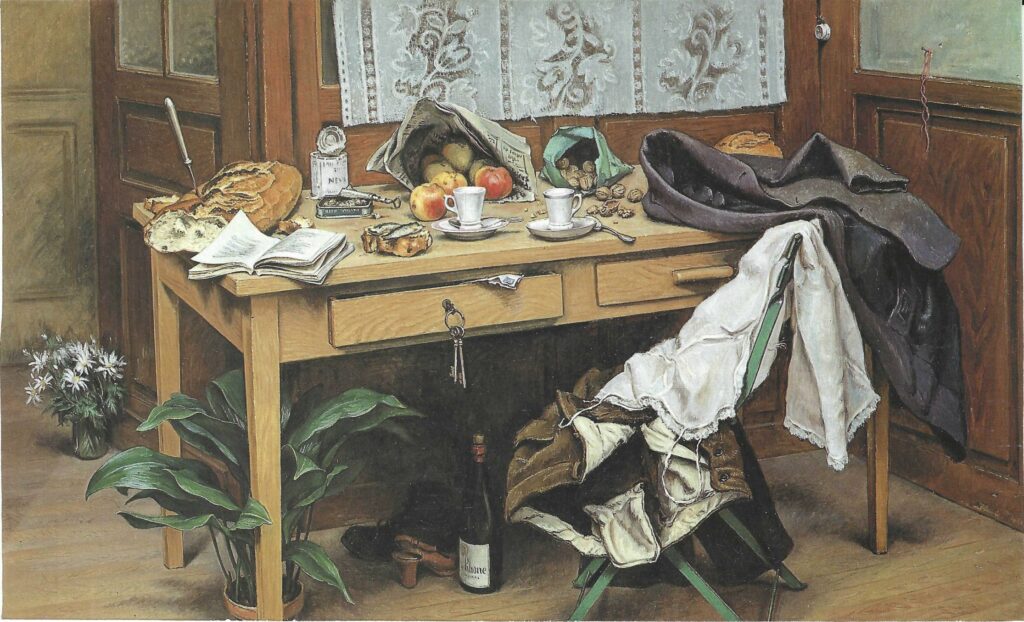

In this same year 1948, Hélion also produced twelve still lifes. In these twelve works, the presence of man is never far away: suggested by bowler hats or umbrellas, he is also suggested by pumpkins (of which Hélion notes: “the carnal sense, the dazzling heaviness … the reclining flesh, the open belly… “) and by the loaves of bread (which Helion compares with “carrying sexual mouths “).

La nature morte à la citrouille from the National Contemporary Art Fund is particularly eloquent regarding the relation between man and object. Including a pumpkin placed on a table, an umbrella, a boot, a newspaper, a bread and a letter addressed to the painter.

1948 – 1949

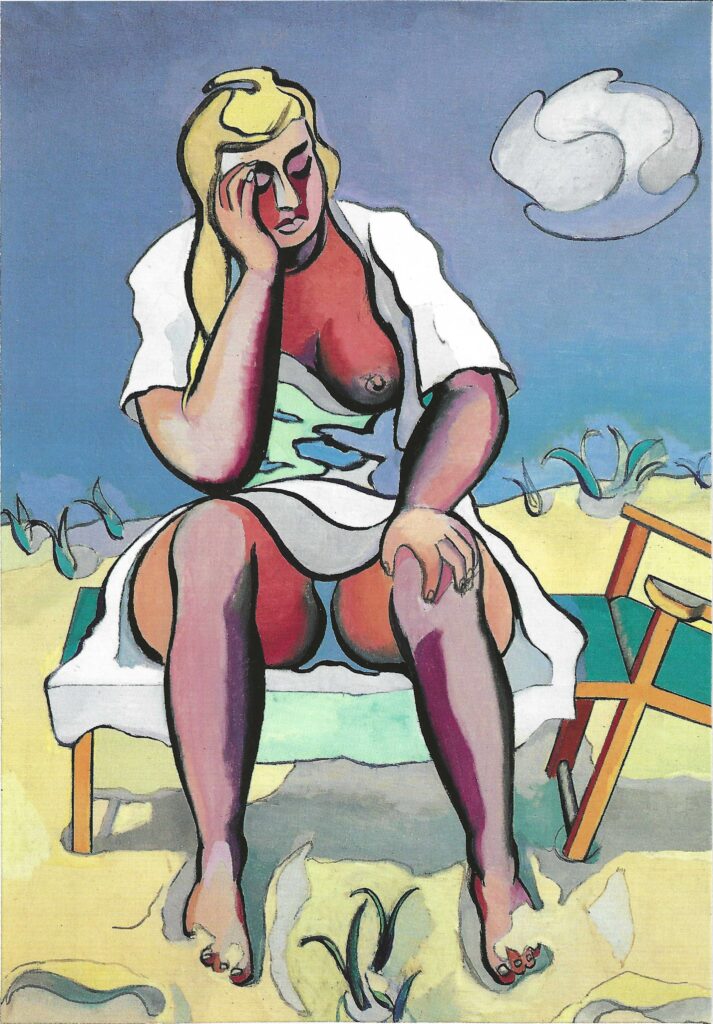

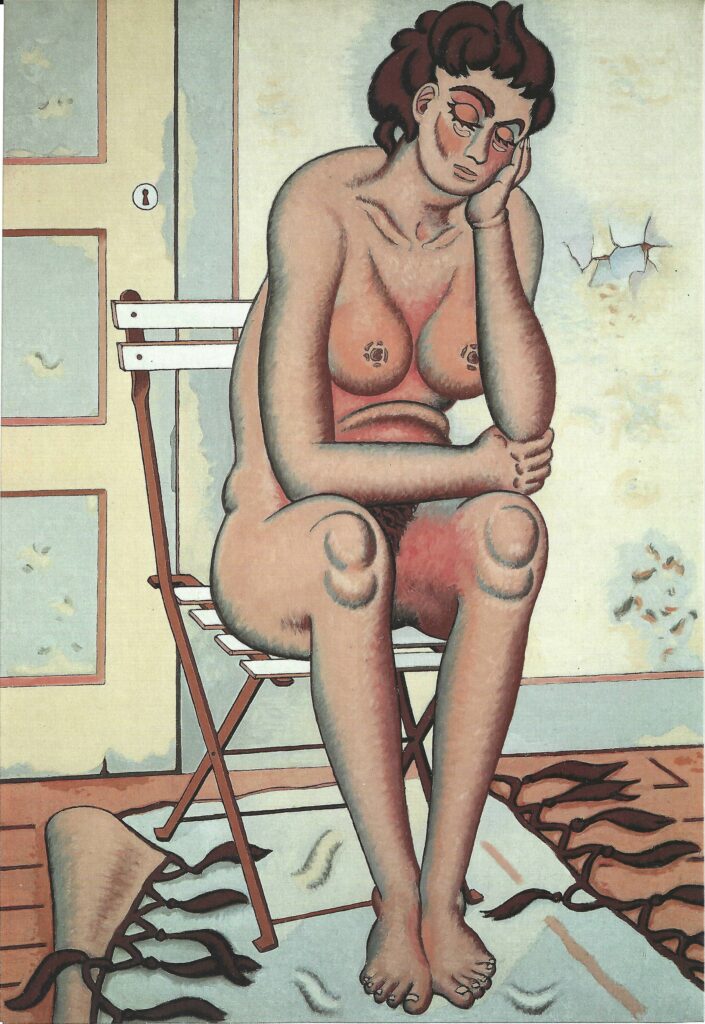

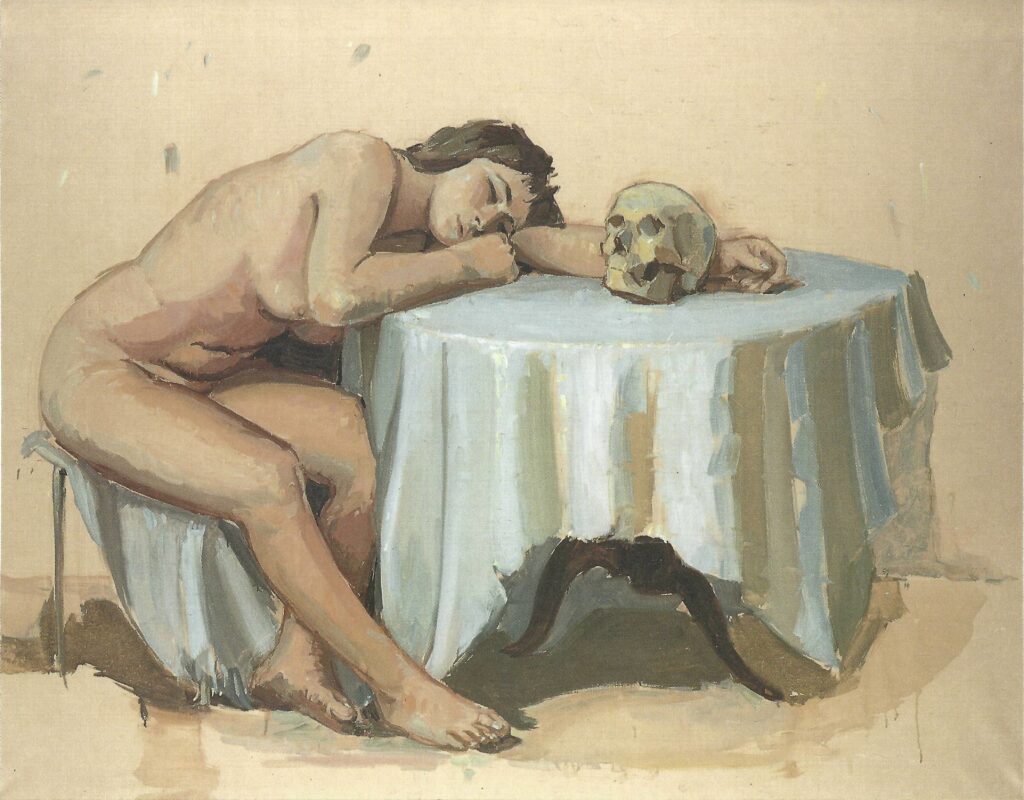

From October 1948 to October 1949 Hélion produced the thirty-one female nudes he describes in detail in the Journal des nus. From the outset he made his point clear: “Nudes, flesh, temple of flesh… and warm and firm flesh, the great rhythm of all the gestures “.

The first thirteen compositions represent a solitary nude seated on a bed or more rarely on a chair. They are generally called Filles temple. Their feet are together, the knees more or less apart.

One of the forearms, bent vertically in line with the leg, supports the leaning head. The other forearm rests horizontally on both knees like the lintel of a temple.

The last fourteen paintings in the series of nudes represent reclining nudes called by the artist Nus étoilés. The nude is lying on a bed, arms outstretched from the thorax and hands on the head and / or stomach. One of the legs is extended, the other bent. The triangular spaces released by the position of the limbs form the branches of a star. Most of the time, everyday objects surround it, evoking the human presence: bread, shoes, pants, jacket, glove, tea towels … Very generally a rug is spread out perpendicular to the bed.

Between filles temple and starred nudes are interspersed four multiple compositions, two represent four seated nudes, two combine a reclining nude and a seated nude.

Special mention to the last of the starred nudes, a large work of 2 m x 1.52 m brilliantly closing the composed scenes in a masterly way in 1950 and 1951. Here the starred nude is lying in front of a large white drapery that separates two windows behind which appear from the waist up a smoker and a newspaperman.

1949 – 1951

Between October 1949, the end of the Journal des nus and October 1951, Hélion produced around thirty paintings; they are first other female nudes, then successively the men on the benches and the recumbent figures, the models and composite scenes in which nudes, recumbent figures, newspapermen and seated men combine to represent the world.

Two new types of nudes appear: a dozen works in total.

The inverted nude, stylistically close to A rebours is depicted vertically lying on its back, upside down, the opulent hair spreads freely, the legs are open in a V, the feet meet.

The barred nude is seated on a chair, the legs are crossed, one of the arms crosses the chest to join the opposite leg; his fist supports the other folded forearm which himself supports the head.

The recumbent figures appeared in 1950. They symbolically embody the poet, the one who, standing apart from conventions and constraints, gazes with wonder at life. He is also the resistant, the incompatible, the painter’s blood brother. He is hostile to all enrollments, all pretenses, all prohibitions. With the exception of two works, one of which is in the Zervos collection in Vezelay where he is represented on a bench in a public garden, he is always associated with female nudes or a newspaperman. Dressed in pants, a white shirt and a jacket, he is still barefoot.

The last group of works relating to this great project of describing man as a “monument of oneself” is the series of mannequineries which comprises six works, three in size 81 x 100 cm, three in size 130 x 162 cm. In a window appear two mannequins, in front of this window, a recumbent figure or an umbrella evoke the human presence.

“I had always admired the mannequins in the storefronts making gestures […] These mannequins appeared to me to play a whole theater behind the window, a theater of elegance and manners. There was also a way of preaching accomplished by their gestures”.

We see this gesture gradually taking place in the six compositions. In the first three, a male mannequin is accompanied by another headless, armless mannequin. If in the fourth work, the second mannequin found head and arms, it is only in the penultimate (Museum of Modern Art of the city of Paris) that the characters begin to adopt the gestures of speakers, gestures which in the last composition (Vaduz Museum, Lichtenstein) lead them to a dialogue, the noise of which awakened the recumbent lying at their feet.

The series of works that can be linked to the theme of “the man as a monument to oneself” concludes with a masterly piece L’allégorie journalière, a large charcoal enhanced on canvas measuring 1.60 m x 2.10 m started in June 1951 (collection Zervos in Vezelay). Bridge thrown between the works of yesterday and those of tomorrow, he associates some of the archetypes that appeared between 1947 and 1951 (newspapermen, mannequins, nudes, seated man) with a newcomer in the world of the painter: the sewerman who we will find several times thereafter, notably in Le triptyque du Dragon from 1967.

1951 – 1955

Works from 1947 to 1950 will be exhibited around the world. Unfortunately, they do not meet with the expected success. “1951: another start date, my five exhibitions of 1951, all superb, had been perfect failures. In London as well as in New York, Venice, Milan, Rome, people did not understand my theater of figures and objects “.

This restart will first be in November – December the series of chrysanthemums (mourning for his illusions, mourning for his ambitions?). Then other flowers will appear: geraniums, anemones, yellow leaves of chestnut trees. Then will come still lifes, most often placed on a pedestal table. This is the era of breads, an object to eat marked with human hands and wounds, pumpkins (a theme that was omnipresent until the last days). “I need to work with the flesh, with the enormity of this vegetable”.

Le goûter of 1953 with its meticulous description of the reliefs of a frugal meal based on sardines, apples, nuts and condensed milk is emblematic of this period. Poverty to be sure, but also the wealth of the fortune of the bodies that were found and left their messy clothes there.

Bodies, women’s bodies … another way to make your ranges, to reclaim one of the most classic themes in the history of art. What could be more classic, what could be more attentive to reality as if man wanted to step aside behind the perfection of nature?

It’s the perfect body of l’Odalisque of 1953. It’s the muscular body of the Acrobat who was once the model of Helion standing next to the loaves of bread at the Tate Gallery in London.

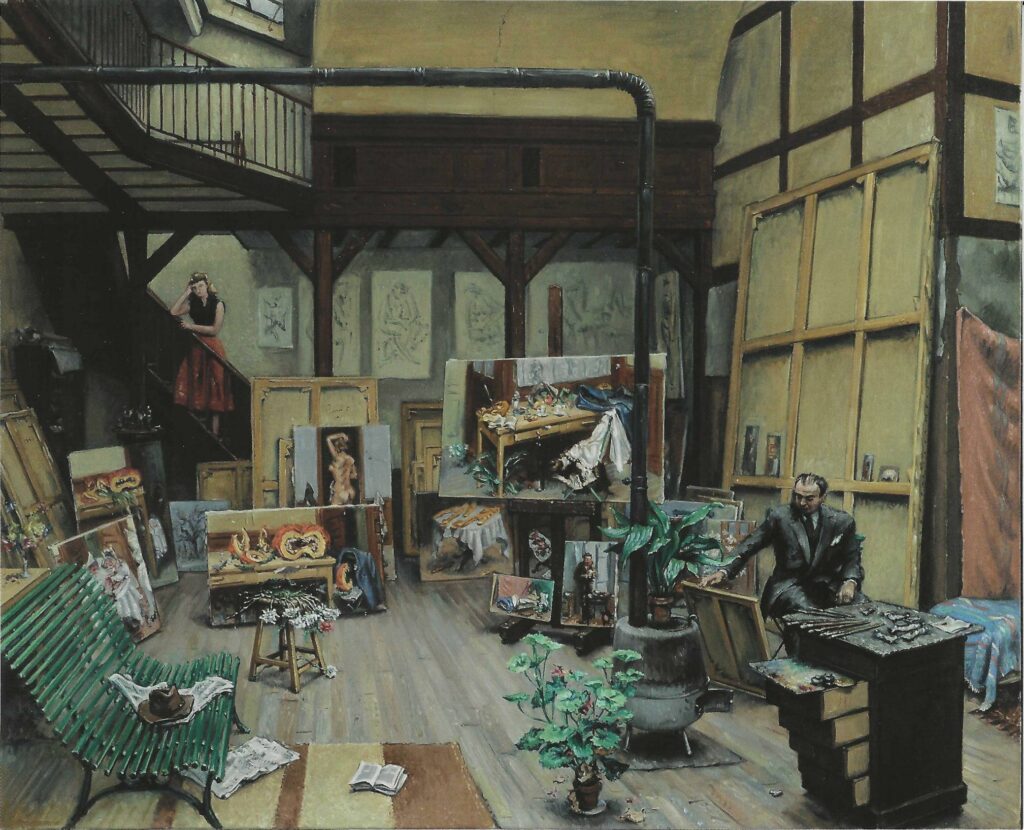

Another classic subject is L’Atelier. It is the studio on the avenue de l’Observatoire which appears in two almost concomitant versions from 1953 – 1954. A first version shows a panorama of his production for the year (Dos aux pains, Le goûter) and two characters that are close to his heart: his wife Pegeen, daughter of Peggy Guggenheim and his faithful friend and collector, magistrate Pierre Bruguiere. The second painting is centered on the painter and the finished works are turned facing the wall. This patient work of personal questioning, supported by the good reviews that accompanied his exhibition in December 53, will happily influence his morale. In March 1954: “At last morale is rising. “In May 1954 he exclaimed:” Suddenly it is as if my genius came back from a long journey where he had enriched himself … I am delivered from the long submission which bowed me before things for three years.” And in fact, this revival symbolically signaled by Les bourgeons bursts with the joy of the Arums whose whiteness floods the studio with light, where two fragments of abstract works appear, including Figure tombée.

1955-1958

However, Hélion, morale returned, has not given up perfecting his approach to things and beings, always tending to be as close as possible to reality, he goes on the same picture or represent the same subject in several attitudes (Couple au parapluie 1956, Portrait de Pierre Herment 1955) or as in Grand Brabant of 1957 (Zervos collection) a central subject completed at the top and bottom of partial approaches of the same theme. “I lined up like a kind of predella, a series of small studies of all possible cases: cases of lights, cases of angles, ideas, dreams”.

The studies made on the motif in the Jardin du Luxembourg and in the Jardin de l’Observatoire which is its extension, are numerous in this period and find their culmination in Le Grand Luxembourg (1957 University of Illinois) where, around a bench, central character as it was in La grande journalerie of 1950, the friends of Hélion meet again. There is a large ganache version (4m x 3 m in the Zervos 1955 collection) where all the characters are absent; only a cap and a scarf remain witnesses of their passage.

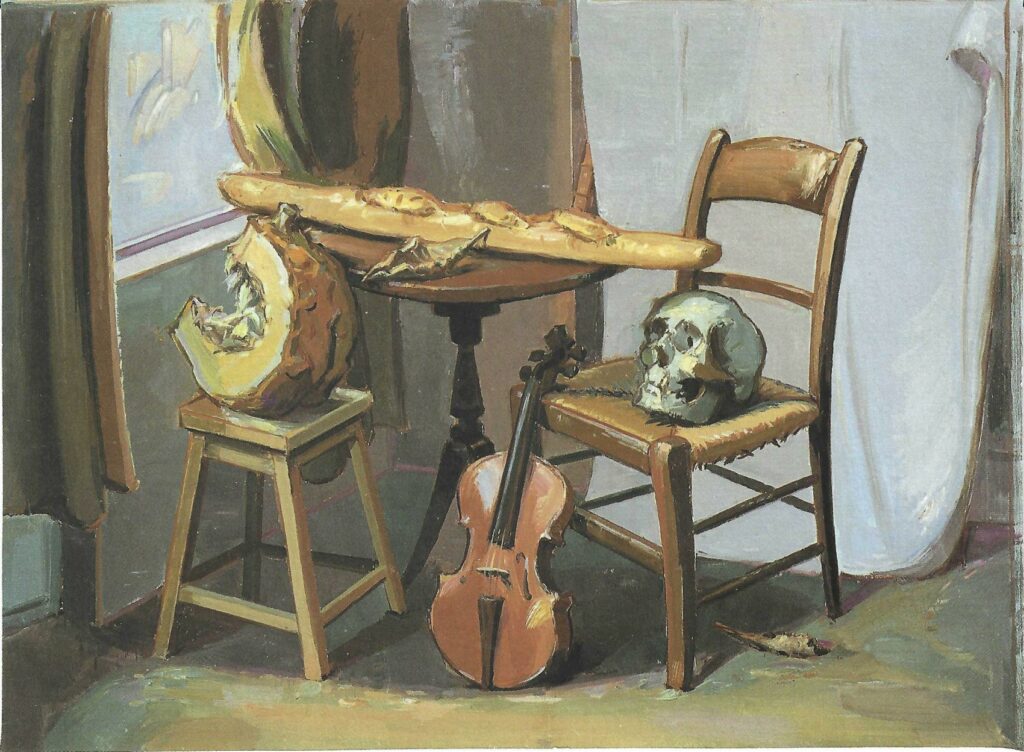

Another new subject in 1957, vanities in which the skulls appear, often confronted with other objects familiar to the painter. The occasion: Friends gave him two skulls in January. He rejoices: “Nothing macabre, feeling of architecture, core, mineral, ordinary and grandiose object … the object which survives for a long time, reassuring. “They will be the subject of numerous studies which find their culmination with the very beautiful Jeune fille et le mort from 1957 treated in a subtle range of ochres and muted blues.

Quator of 1958where the skull coexists with a pumpkin, a bread and a violin is emblematic of the process of creation of Helion. He assimilates, he swallows objects which, either by their form or by their power of evocation, have touched his sensitivity; just as the forms constructed during the abstract period form the canvas for his figurative constructions. In the same way all these objects enter into his world, are combined to infinity, a phenomenon carried to the climax in the works of the last years 1978 – 79, Suites pucières, Escalades chapelières which find their highlight in the last triptych Le jugement dernier des choses from 1979.

1959 – 1961

At the beginning of January 1959, Hélion decided to make eleven portraits of his poet friends or seated collector. “I feel them in me with the violence and the certainty that I experienced in 1935 when I began the abstract series of Figures debout which I said would be family portraits”. While there are many preparatory studies, only five large portraits, all in shades of blue, were completed. They belong to the Montauban Museum.

It is also in 1959 that the roofs will appear in the painting of Helion. The roofs he sees from his home / studio in rue Michelet. Announced by a large charcoal from 1953 acquired by the National Museum of Modern Art, which appeared as a decorative element in 1958 in La citrouille et son reflet, they are the sole subject of multiple representations between 1959 and 1961. In line with the roofs, from 1960, Hélion was interested in the skylights that illuminate a corner of a room where still lifes are recomposed on the pedestal table. In many of his still lifes, a toy soldier stands next to a trombone. Particularly harmonious, a work from 1960 where a cello converses with a soft hat, a cabbage and a pump.

Hélion left the studio of rue de l’Observatoire in 1957 (where L’Atelier was painted, as mentioned above) and now works at rue Michelet studio, the entrance to which is in the heart of the roofs and preceded by a footbridge. In 1961-62, several paintings represent it with family scenes bathed in music that take place there. The titles of these works are evocative: Concerto pour les toits, Rapsodie sur les toits, Cantate sur les toits.

In 1961, the painter also painted two large canvases in the Luxembourg garden, rich in walking and playing characters. L’été de la Saint-Martin and Joueurs de cartes au Luxembourg announce the painter’s return to the spectacle of everyday life.

1962 – 1967

Back in Paris, again amazed by the spectacle of everyday life in the street, he again experiences the feeling that made him write in the 1940s. “I dream of a Sistine Chapel in today’s costumes and forms”. This dream of allegory, of everyday mythology, it will first be in 1963 Les bouchers who will embody it. He goes to Les Halles, he sketches these “meat carriers” of which he says: “This motif is one of the most perfect that I have touched”.

Three magnificent paintings are made. The glowing carcass and the butcher in a white overall fraternally united seem to sketch a dance step that stabilizes the ocher background of the composition. The National Museum of Modern Art has one called Monument pour un boucher.

Another character in this allegory: the old women who carry their tote bags, which Helion calls the tote bags women. “Carriers of shopping bags, shadow figures, Fates, choir, witnesses, midwives, mourners. Nothing sad about it all”.

From 1964, Hélion’s vision spread, broadened to the whole of the street spectacle animated by anonymous figures, witnesses or actors of this modern fresco that he dreams of building. In 1964, they will be the street merchants, the flower shops and the butcher of the Museum of Modern Art of the city of Paris and its explosion of reds where the flowers of the stall echo the carcass carried on the shoulder of the butcher. In 1965 – 66 in a series of canvases with evocative names (Les attendants, Les dépassants, La suite traversière), the painter was interested in passers-by: long anonymous silhouettes in dark, structured clothes, supported by a white line which indicates its frame, they wait for the bus, they get off, they cross the road and go about their business.

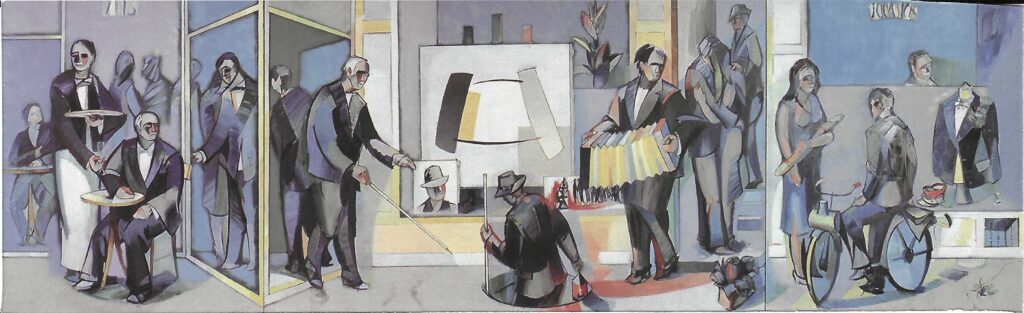

In 1966-67, Hélion began to paint the series of cafés. The idea is that of a place where the passer-by stops to contemplate the spectacle he was bringing to life in the series of rues.

But it is also a stopover, a retreat to an anonymous place. The showcase is preponderant, like an aquarium, it isolates and protects. In several of the works in this series appears a new character who will often be found in later works: the road worker who smashes the road with a high lifted pick which is reminiscent of the balance wheel of the 1933 Equilibres.

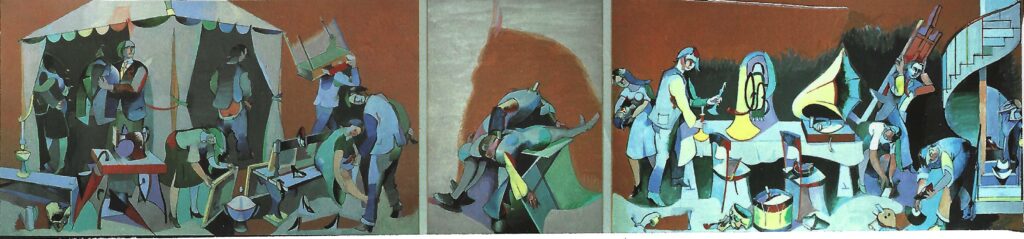

1967 was a pivotal year for Hélion. First on a personal level: a severe allergy to solvents forced him to give up oil painting in favor of acrylic. On the pictorial level, on the occasion of an exhibition at the Galerie du Dragon, he produced his first large triptych which will take the name of the gallery which exhibited it: it was designed according to the layout of the gallery and it occupied three walls.

As L’allégorie journalière of 1951 did in its time, the triptych summarizes and represents all the themes and figures on which the artist worked. Under the crossed gaze of the seated man from the café series and the accordionist who appeared in the “Rue des quatre saisons”, the sewerman (also present in L’allégorie journalière) comes out of his hole. We will find him often now. Hélion explained his symbolic role in 1984: “The sewer hole seems to me to be made for poets who go to see what is at the bottom of the earth and who having seen it come back to tell you”. A blind man, who appeared for the first time in L’allégorie luxembourgeoise from 1965 (the year when for the first time, the artist evokes his sight problems, through multiple operations, will lead him to virtual blindness). The hole that he will undoubtedly avoid here, he will end up falling there (Breughel reference?) in the Suite pour le 11 novembre, this hole that a worker digs with a shovel, brother of the one we saw attacking the macadam in the series of cafés.

1968 – 1970

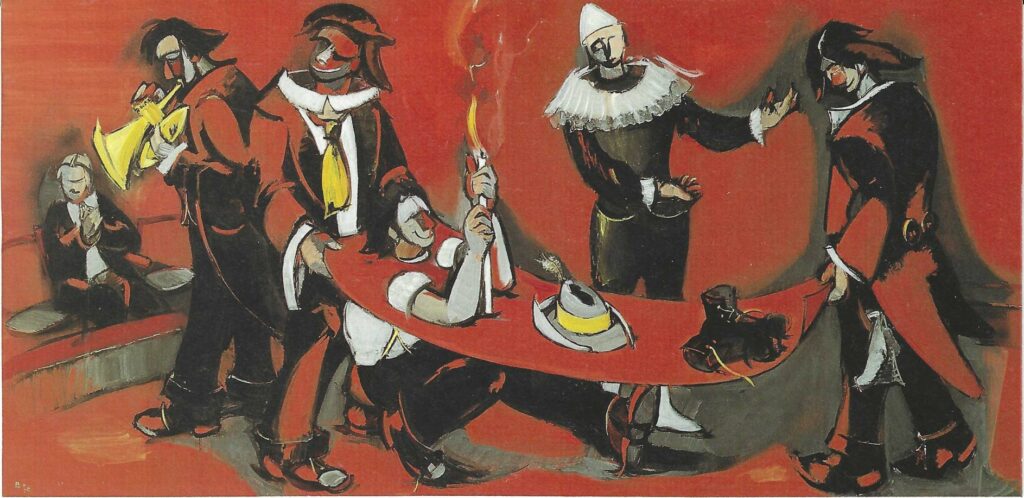

Two major themes emerge during this period. It was first of all the events of May that could not leave this kind-hearted anarchist indifferent. He is a faithful witness to this in Choses vues en Mai, the second large triptych of the same size as that of the Dragon. The red and black flags contrast with the tricolor flags of the tote bags women framing a young girl astride a protester’s shoulders in front of a burning bench. “The republic of the tote bags women disturbs me as much as the girl astride the man in the red panties”. Two smaller canvases, Vanité de Mai and Vanité de Juillet, designed as essential complements to the triptych, take up some of its elements.

The circus is the second major theme of those years, thought from 1967. “The circus is going to be a big deal for me: the place where ordinary people do extraordinary things … about the circus, what it means, I could end my life”. His final point of accomplishment was in 1970: Supercherie jaune and Supercherie rouge. On the shroud carried by accomplices is represented the body of Augustus of which only the head and arms protrude while the legs are on the ground.

“I see in it,” said the painter, “a representation of the state of the art and even of human life in general”.

Third subject developed in 1969-1970, subway entrances and exits. This is another variation on the theme of the hole, the sewer man’s hole, the roadworker’s hole, conceived as an exploration of the depths whether it is the crowd that comes out like a flood or the passer-by who goes down there alone.

1971 – 1972

The eye problems that started in 1965 worsened considerably in 1971: in May, retinal hemorrhage; at the end of the year, double cataract surgery. Hélion will remain three months without being able to work. The theme of castles, in fact a perron on the railing of which rests a young blonde woman, is the major theme of this year 1971. It allows the artist to reconnect with the theme of the hole. In front of the perron are the worker with the shovel (Pelleas et Melisande), the diggers (Le château bleu) and the sewerman (Le château).

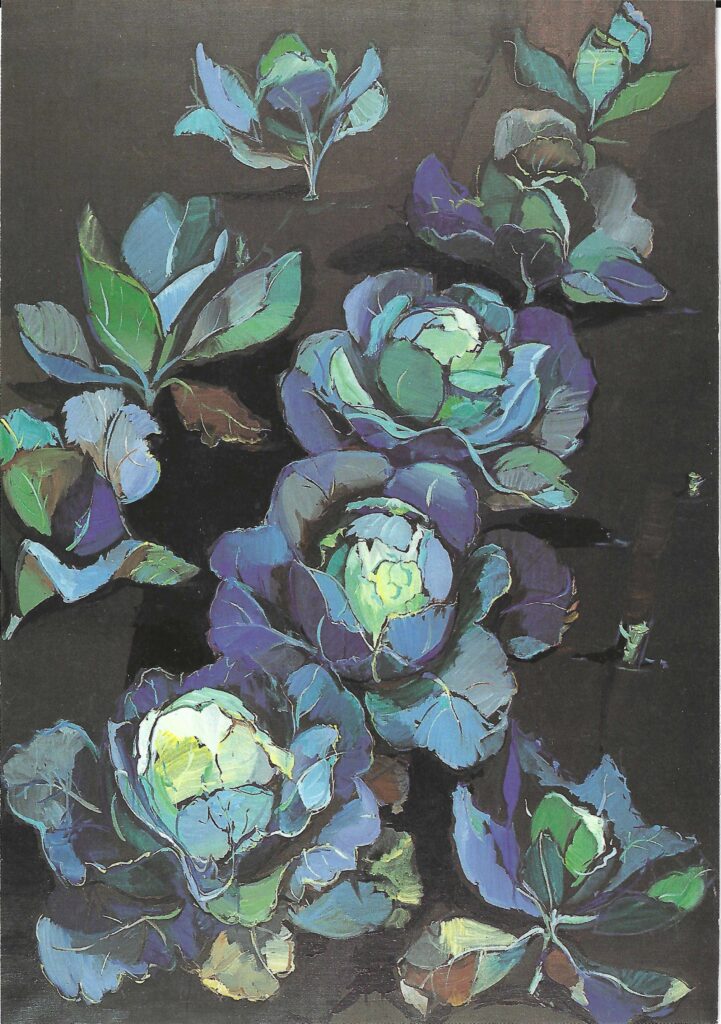

In June 1972, while Hélion was in Bigeonnette (property near Chartres, purchased in 1962), the discovery of cabbage as an object of painting plunged him into joy. “Jacqueline (the painter’s wife) arrived at the studio with a cabbage hugging her chest. It was so beautiful that I pastellized it immediately. Each cabbage seems to me a sublime natural abstraction where this song, this long phrase that haunts me, is played leaf by leaf, from one cabbage to another”. This humble and vegetable form will be the subject of numerous drawings and paintings and will culminate in the magnificent Le Carré de choux, which was very popular at the National Museum of Modern Art exhibition in 2004-2005.

1973 – 1974

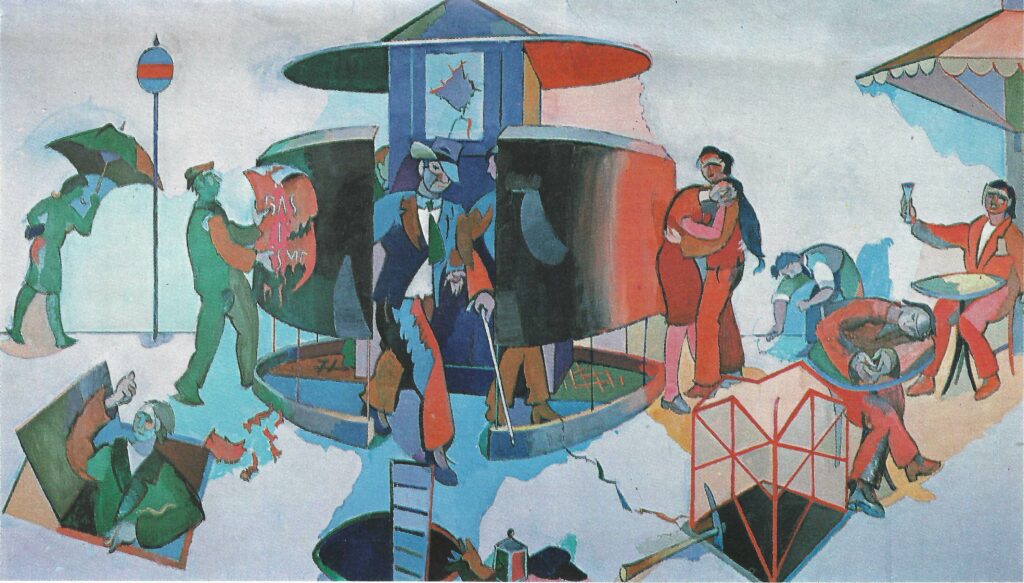

The Hélion couple now live almost permanently in Bigeonnette. In February 1973 Hélion had new eye problems: bursting of the left retina, glaucoma in the right eye. From that time he can hardly see more than one eye. He will devote most of his research to the observation of these markets found in small provincial towns where pumpkins, cabbages and leeks cheerfully sit alongside shoe stalls, clothing of all kinds and lawn mowers. This will lead in 1974 to a third large triptych, Le triptyque du marché, where all these themes are linked and interwoven. The woman in the red nightgown is found that same year in one of the strangest, most disturbing paintings of Hélion Mathilde, son ombre et son reflet.

Does this blonde woman take her dress off or put it back on?

Is it her lover stealthily slipping right into a bluish light? What does this lit candle holder tell us? An important element of this painting is the mirror in which Mathilde is reflected. This reflection is also symbolically like the hole of the diggers or the sewerman. Another way to grasp the world, to hunt down the truth through appearances. This is a recurring approach at Hélion. Wasn’t he already saying about his abstract period: “I wanted to grasp reality through the heart, through its hole”. We will find this reflection even in the last works, this reflection in which the painter scrutinizes his image, that he is losing sight of (R. pour Requiem 1981, Suite vaniteuse à Atelier 1982).

1975 – 1979

The themes tackled are numerous during this period of five years: they are successively the book boxes of the quays of Paris, Boîtes de Pandore, Boîtes à curieux. Lobsters when the painter is in Belle Ile: this subject evokes for the artist the theme of the crucifixion: “The theme of the crucifixion haunts this whole lobster saga; the red lobster, the dangling claws and two joined legs begs the Virgin Mary”.

Then come a series of canvases in which the hook wearing clothes from the entrance in Bigeonnette plays the main role and where we find the reflection (Le perroquet et ses échos). Then there are works on November 11 (Suite pour le 11 novembre, 1975 already cited about the blind falling into the hole in the terraces) followed by Pantalonnades et Jambages, a comedy series where nudes are seized in the process of putting on pants that is sometimes the only actor in certain paintings. The street urinal of Paris, now practically disappeared, are the theme of a series of works whose culmination is a large canvas called La ville est un songe completed at the end of 1976. Title chosen by analogy with the play by Calderon La vie est un songe.

The blind man emerges from the central aedicule, three holes threaten him: the blower hole, the digger’s hole, the sewerman hole; around him are regular characters from the Helion theater. Embracing couple, coffee drinkers, passer-by with an umbrella, poster maker where one can decipher “down with (fasc) ism” as one could read “down with w (ar)” on Les mannequineries de 1950 and on the banners of Choses vues en mai.

From 1978, Hélion summons all the objects that have animated his works since his return to figuration and composes tasty assemblages which he calls Suites pucières. As an example, Suite pucière n ° 1 thus assembles from left to right a bucket, a mannequin’s hand, bones, a hat, a kepi, a coffee pot, dumbbells, an inverted painting, the outline of a white soup tureen on canvas and sink taps. The series will conclude with the painter’s last great triptych entitled Le jugement dernier des choses with a heterogeneous assembly. Objects come to join characters already known (an embracing couple, a woman trying on clothes, a salesman) or which will be the subject of later paintings such as the painter carrying his easel on his back which we find in the very beautiful Parodie grave of the National Museum of Modern Art (1979). It is again the theme of the crucifixion, of Christ and of the two thieves that these three painters bring up their easels. It is also, more daily, the vision of the painter attached to his canvas and his brushes, always in search of the finally accomplished work, but also confronted with material difficulty and criticism. Passion, founding myth and passion for the work carried out: the double meaning of the word could not have escaped Helion.

1980 – 1983

An idea is close to his heart at the beginning of the period; the figuration-abstraction debate is an illusion. It does not matter whether one chooses to treat a subject in a figurative or abstract way if one knows how to extract the deep truth from it, “the sign it makes to the rest of the world” is the meaning that must be attributed to the series envisaged in 1979 but completed in 1981: two painters installed in front of a nude represent it in an abstract way or, on the contrary, turning their backs to it, give it a figurative vision (Le songe, Le Réel et le songe). For Hélion, the dream is another way of making reappear the truth hidden behind appearances: “I draw with my knowledge, I color with my passion, I compose with the dream”.

Subsequently, faced with a view that continues to decline, Hélion will revive the characters of the 1940s by giving them new colors: “I painted panties that were not red and women in purple. who were naked because such was my good humor, such was my way of singing the happiness of one and the other”. In the Nouvelle scène journalière “coming back from the 1940s”, two newspapermen go to each other like armored warriors with their newspaper: “Are they fighting for this nude whose splendor is green? ” In the Second royaume a sewerman is about to come and whisper sweet nothing to a purple nude while a pickaxe busts himself under the gaze of a seated man. Remake, with an evocative title, takes up the theme of the Dormeur et le nu from 1947: a recumbent figure is lying in front of a nude at his window.

“From pink that I found a little indecent, the flesh became purple like the dream … thus old signs are used to grasp new situations. It’s always the same, otherwise. “

One of the artist’s last works deserves to be cited as it illustrates the youthful spirit that Helion has retained. Last snub and eternal beginning, the Relevé de la figure tombée shows us, under the watchful eyes of a quarter of pumpkin and a hat, a kneeling man busy straightening this Figure tombée, symbol in 1939 of the abandonment of abstraction.

It is this youthful spirit, this sense of effort, this search for the absolute that we must remember.

Hélion wrote in 1983: “An ancient tree, torn by lightning, I still shelter charming birds”.

Many of us remain sensitive to it.