Jean Hélion

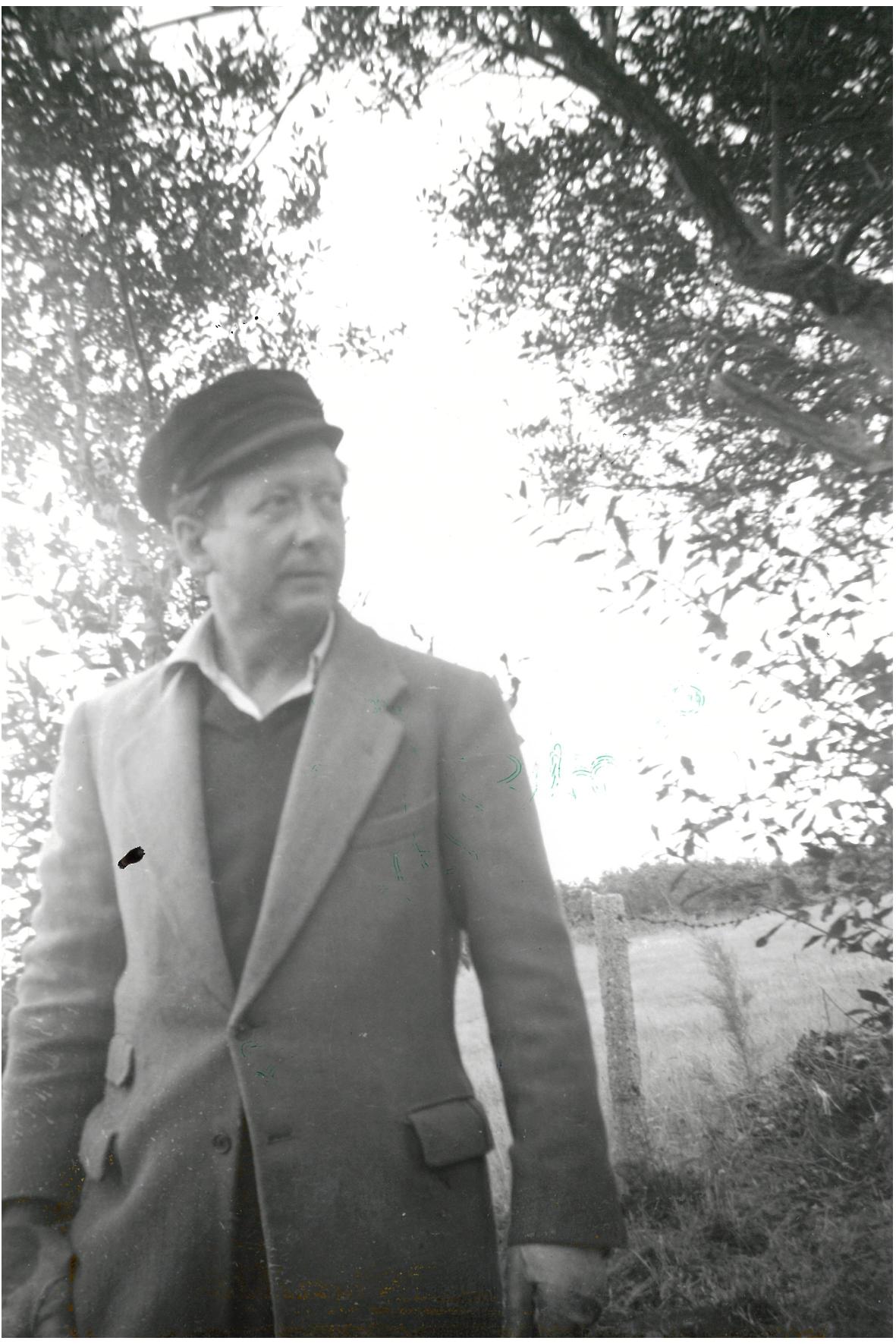

Jean Hélion was born in Couterne (Orne) in a family of small people exercising various trades: a grandfather sawyer, another clog maker, a father cab driver then driver, a mother seamstress.

Thanks to the insight of a schoolmaster Hélion was directed to an engineering school in Lille (L’Institut Industriel du Nord), which he left quickly enough to try his luck in Paris.

His tastes and his readings led him to poetry. But first he had to go through a period of apprenticeship in an architectural firm.

He learned to draw plans and to carry out surveys of ancient motifs at the Louvre Museum.

It was there that he discovered the world of painting. Decisive shock with Poussin, Seurat and Philippe de Champaigne.

From that moment on, he had to devote his entire life to it.

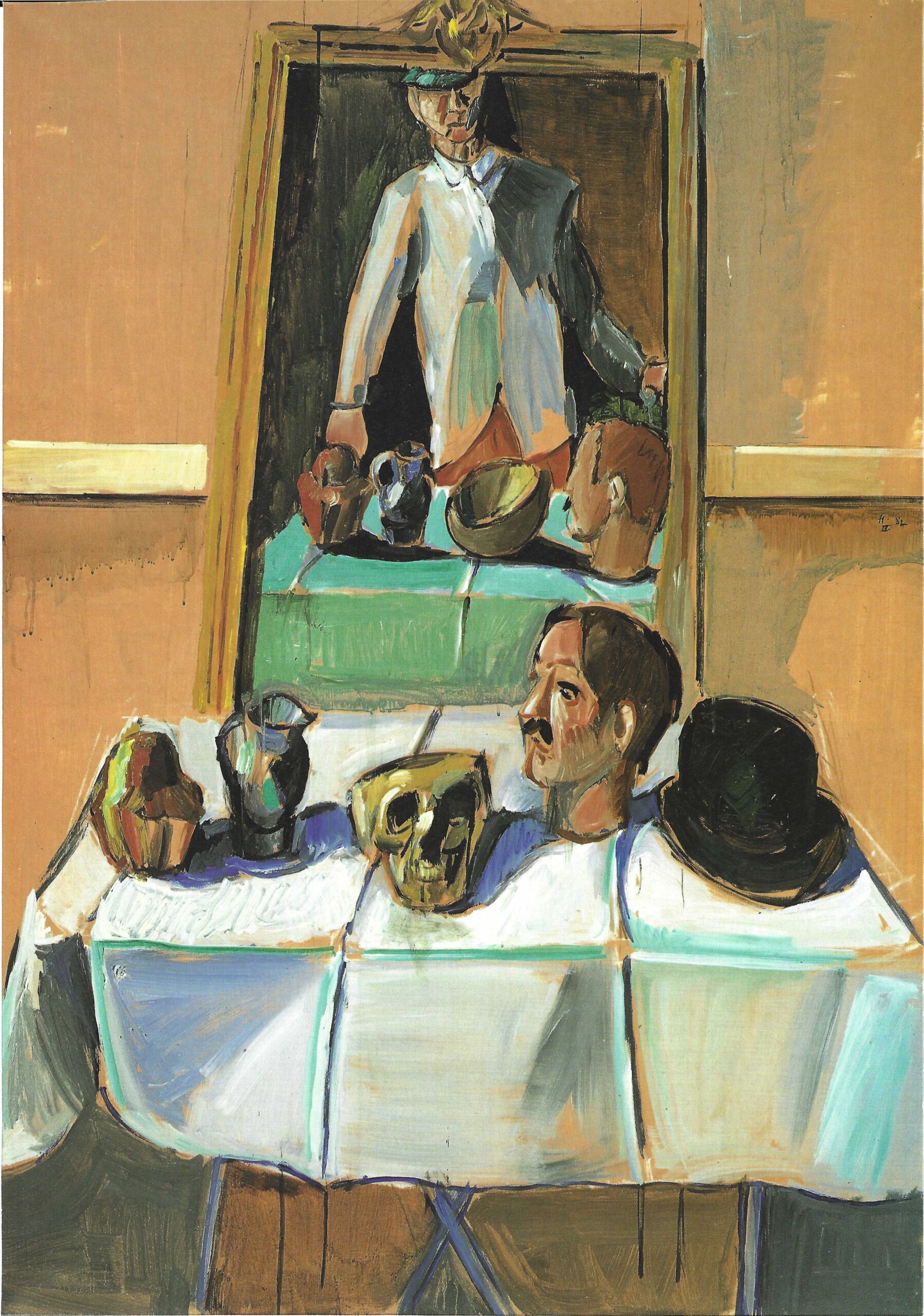

In the twenties he worked on painting in a figurative style, influenced by Soutine.

His first masters were Torrès-Garcia, then Mondrian.

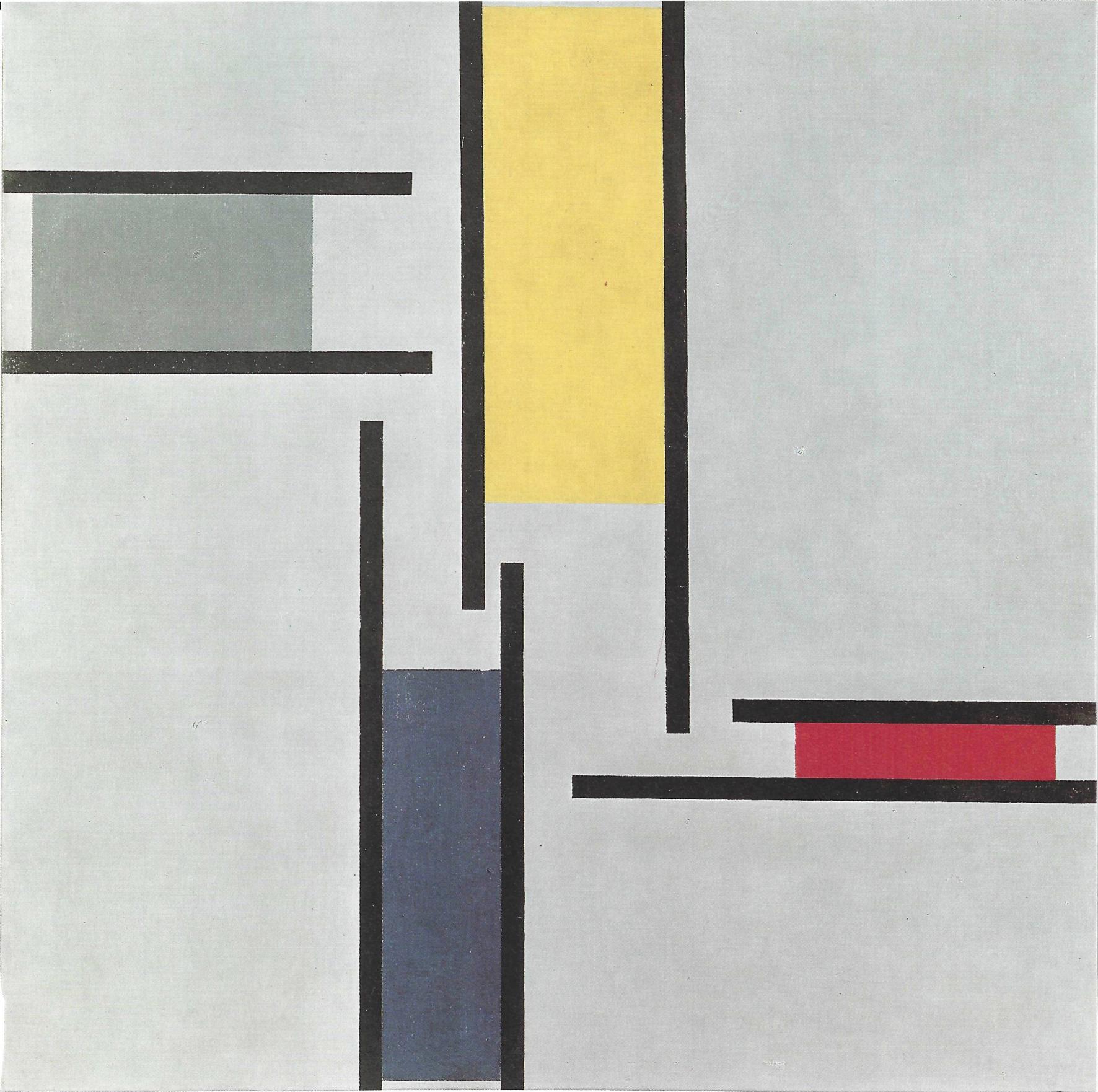

From 1929 to 1939 Hélion undertook a reconstruction of reality, starting from Mondrian’s orthogonals to the complexity of his large abstract compositions (The fallen figure 1939 MNAM-Center Pompidou). With Theo van Doesburg, Otto Carlsundet and Léon Tutundjian, he founded the group Art concret that became Abstraction-Création.

Mobilized in 1939, prisoner of war in June 1940, he spent nearly two years in stalags in Silesia and Pomerania, where he managed to escape in 1942.

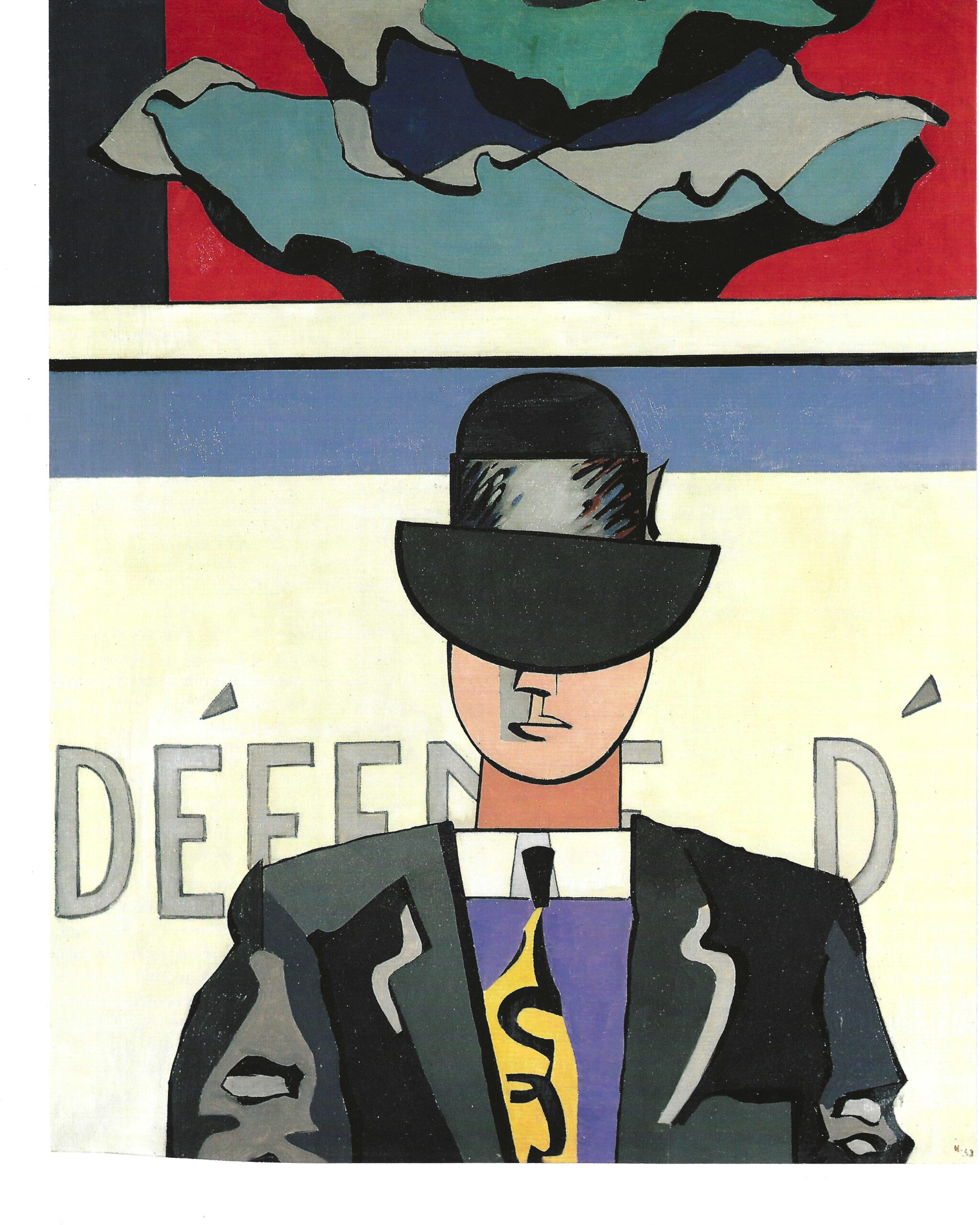

After the war, he resumed his motifs born from his abstract compositions and, always against the grain, developed an original figuration where couples under umbrellas, nudes, window mannequins crossed hieratic figures in hats, dreamy recumbent figures or readers of allegorical newspapers. It won him over ten years of loneliness and rejection.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world was “discovering” abstraction.

Fernand Léger and Christian Zervos encouraged him, however, and a few loyal friends supported his approach.

Finally, in 1962, Hélion gained recognition thanks to an exhibition at the Louis Carré gallery.

Over the next twenty years, Helion’s work was to find its place little by little in museums and in some collections, both in France and abroad.

Despite serious health problems, his production remained impressive (Triptych of the Dragon, 1967 – Triptych of May, 1968-69, The Last Judgment of Things, 1979, among others…).

The brutal worsening of the condition of his eyes will force Hélion to put down his brushes forever in 1983. He devoted the last years of his life to writing several volumes of self-critical comments on his career as a painter interspersed with memories (cf. Bibliography).

Jacqueline Hélion

the paintings

The 1920s

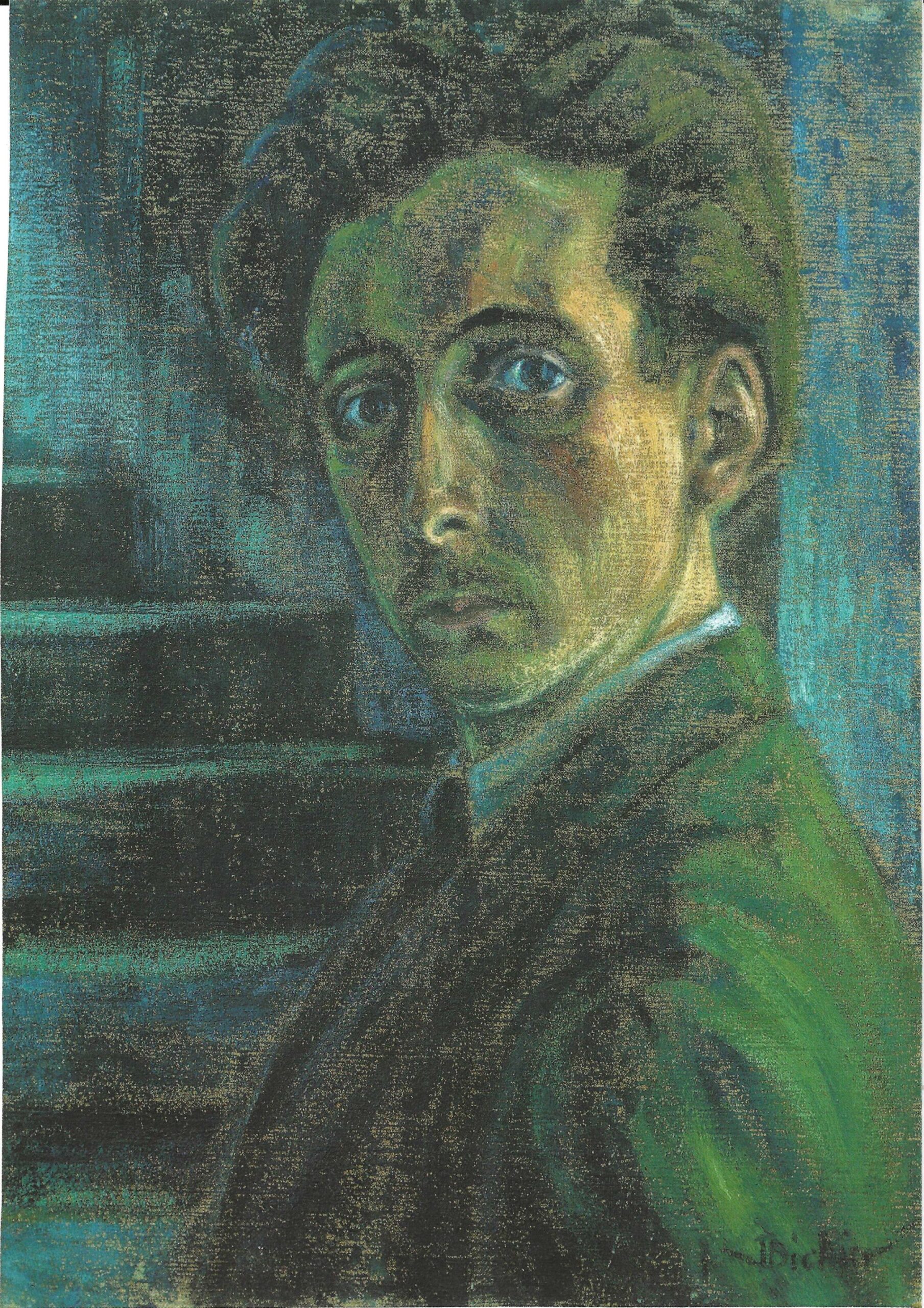

He began to paint around 1923. His early years were an initiatory period for Jean Hélion, as he meets people and exhibits at the Foire aux croutes at Montmartre.He painted everyday objects, table, glass, bowl, bottles, bread.

A certain influence of Soutine's painting can be seen in some of his works such as Homme assis (1928).

The 1930s

With the Uruguayan painter Torrès-Garcia he discovered cubism and surrealism. He turned to abstract painting in July 1929. In 1930, the influence of Mondrian led Jean Hélion towards constructivist abstraction (Composition orthogonale). The Art Concret group founded with Théo Van Doesburg, Tutundjan, Carlsund, manifested a radicalism where the work of art must be entirely conceived and formed by the mind before its execution. This group became Abstraction-Création around 1932, with Arp, Herbin, Delaunay, Van Doesburg, Kupka, Gleizes, Valmier and Tutundjan. This was the period of Equilibres, Figures, Compositions, Ile de France (1935). Figure tombée (1939) closes the abstract period.

The 1940s

The end of the 1930s saw Jean Hélion gradually move away from abstraction with Figure tombée 1939, and his first large figurative painting Au cycliste 1939. On his return from captivity in 1943, men with hats appeared, including Défense d', street scenes, seated men, L'escalier and La Belle Estrusque. A rebours and Les Trois nus are two major works from this period, of which Jean Hélion wrote in the "Journal d'un peintre" (February 5th 1947) that they seemed to him to be "the most complete and brilliant paintings I have done. I would like to be judged on that". In 1948, thirty or so nudes followed, then the six mannequins.

The 1950s

At the end of 1951, a new period with about thirty "chrysanthemums", geraniums, arums and chestnut leaves. He painted from nature and pursued reality as closely as possible, as it can be seen in L'atelier, Le Goûter and Odalisque à l'atelier. At Belle-Ile, there is no shortage of other motifs on reality, Le Grand Brabant, Port-Coton, Paysage.

The 1960s

Hélion is fascinated by the spectacle of the street. Butcher's shops, meat carriers, passers-by, shop windows and stalls fill the paintings of these years. He goes to the circus and paints clowns. The events of May arouse a keen interest from Jean Hélion.